Exploring Russian Romanticism

by Nicholas Keyworth of Revolution Arts

The two works in the 16 June concert by the London Firebird Orchestra conducted by Michael Thrift with soloist Marc Corbett-Weaver typify the image of Russian Romanticism: Two large scale works, emotive and dramatic – written by two self-doubting and angst-ridden composers. Surely we would expect no less from these late 19th century artistic temperaments?

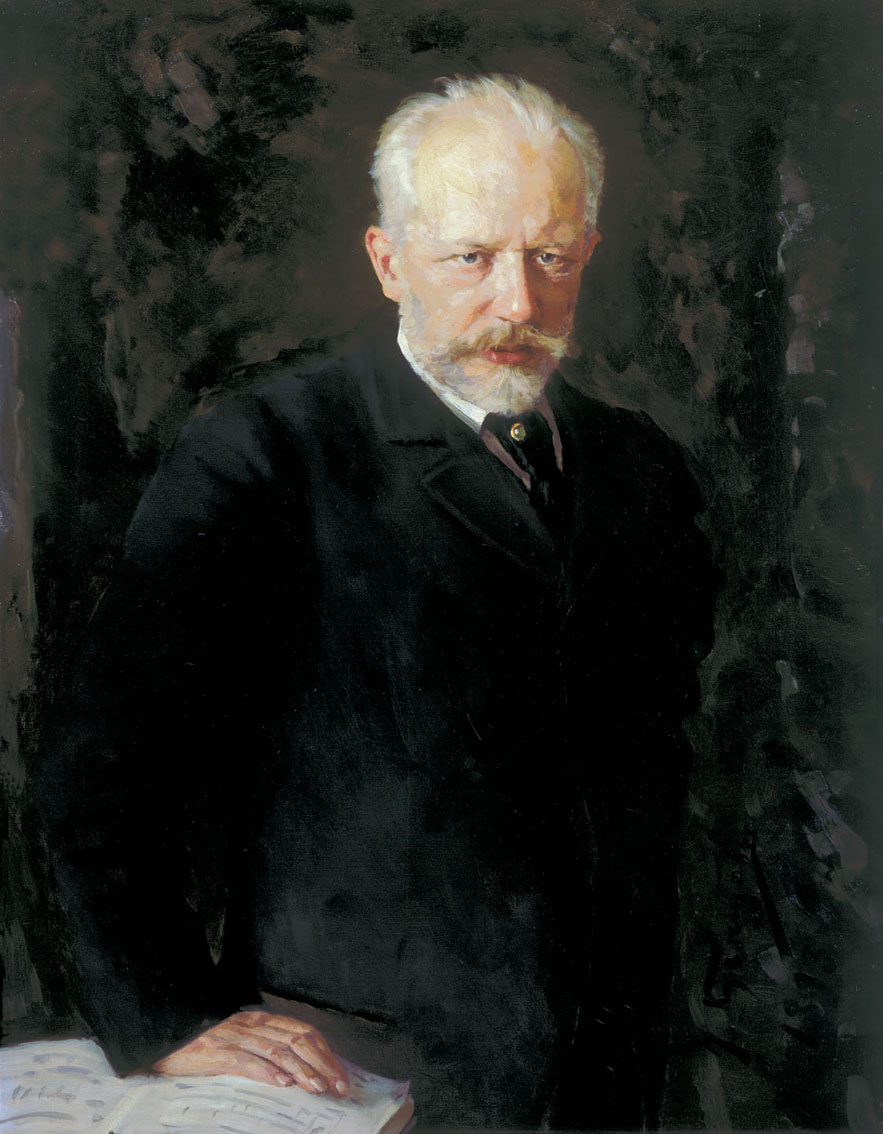

Portrait of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky by Nikolai Kuznetsov

Like Tchaikovsky’s more famous 4th Symphony ten years earlier, his 5th is also associated with ‘Fate’ after their dark brooding themes and declamatory musical statements. A month before he started composing the 5th symphony, Tchaikovsky wrote some ideas for a work in his notebook including the words “… a complete resignation before fate, which is the same as the inscrutable predestination of fate …”

The initial critical reaction to the 5th was not at all favourable and at times hostile particularly in the United States where a reviewer for the Boston Evening Transcript wrote:

…”sounds like nothing so much as a horde of demons struggling in a torrent of brandy.”

Even in Russia, Berezovsky wrote: “The Fifth Symphony is the weakest of Tchaikovsky’s symphonies”

Tchaikovsky’s signature

After the second performance Tchaikovsky wrote, “I have come to the conclusion that it is a failure”. He was still recovering from a turbulent time in his personal life following a disastrous marital situation, increasing self doubt over his sexuality and battling with heavy bouts of depression. Tchaikovsky’s creative drive was becoming increasingly autobiographical and expressive with great passion and forcefulness – even violent in his musical outbursts.

Rachmaninov at the piano

Rachmaninov too had been suffering from clinical depression and writer’s block for years following the 1897 premiere of his 1st symphony which was derided by contemporary critics. His second piano concerto was a huge struggle for Rachmaninov to complete but with the help of hypnotherapy and psychotherapy from his physician Nicolai Dahl the final success of the concerto did much to restore Rachmaninoff’s self-confidence.

Rachmaninov’s signature

The usual Germanic formality associated with large scale symphonic and concerto works did not come easily to the Russian Romantic composers whose natural instinct was to write music which was less structurally restrictive, primarily evocative and expressed personal emotions.

Romantic music in Russia was heavily influenced by its literature with writers such as Alexander Pushkin whose writings such as Ruslan and Ludmila and Eugene Onegin directly inspired musical compositions. Other Russian poets such as Mikhail Lermontov and Fyodor Tyutchev respectively explored ideas of a metaphysical discontent with society and self, and descriptive scenes of nature or passions of love.

Alexander Pushkin

So what has made these works the staple of the orchestral and concerto repertoire with two of the most loved and frequently performed works of the Romantic Period?

Well, in addition to these personal – almost autobiographical – journeys through their respective landscapes of passion with moments of anguish and melancholy, both composers had an innate ability when it comes to creating memorable lyrical melodies. Glorious melody after glorious melody flows throughout both pieces. Whether it is the plaintive horn melody in the second movement in the Tchaikovsky to the almost divine dialogue between orchestra and soloist in the case of Rachmaninov. It is through electric spine-titling moments such as these that these two works are, without doubt, amongst the greatest pieces ever written.

Marc Corbett-Weaver, soloist in Rachmaninov piano concerto no 2